MIRROR OF INFLUENCE

Kendalle Getty’s new exhibition, Mirror of Influence, challenges societal constructs of identity and the roles we inherit. The show delves into the relationship between external pressures and self-perception, using sculptural chairs, mirror sigils, and candle installation to explore themes of cultural conformity and the passage of time.

Getty's work examines how social codes and inherited legacies shape our identities, often reducing the complexity of the self. Through the use of mirrors, sculptural chairs, and self-portrait candles, she reflects on the tension between our desire for belonging and the fear of losing individuality. Her art invites viewers to confront the subtle violence of cultural expectations, from beauty standards to the shaping of personal identity, urging them to consider how these forces affect the way we define ourselves and navigate the world.

In Mirror of Influence, Getty also reflects on the inevitability of aging and the ways in which society’s obsession with stasis distorts our perception of self. Her exploration of identity is both personal and universal, inviting viewers to examine their own experiences with the cultural pressures that shape who they are, while offering a space to reflect on the contradictions and complexities of self-representation.

Kendalle Getty is a New York and Los Angeles-based multimedia artist known for her exploration of identity, culture, and memory. A 2010 graduate of NYU’s Steinhardt School, Getty’s work spans sculpture, video art, poetry, and music. She confronts social norms, familial roles, and the complexities of self-representation, creating art that encourages reflection and conversation around the forces that shape us.

Mirror of Influence showed from February 19-23, 2025 at Villa Madrid on the occasion of FRIEZE LA.

The Golden Child

Multimedia

2022

Photo by Esteban Schimpf

Before internet culture, “memes,” as defined by Richard Dawkins in his 1976 book, The Selfish Gene, referred to a unit of cultural information that essentially replicates the function of genes by spreading and transmitting ideas, behaviors, and other aspects of culture between individuals, “just as genes propagate themselves in the gene pool from body to body via sperms or eggs, so memes propagate themselves in the meme pool by leaping from brain to brain via a process which, in the broad sense, can be called imitation” (Dawkins, The Selfish Gene). Essentially, memes socially cultivate traits that would have initially been genetic. Whereas Dawkins meant character traits, with the contemporary normalization of plastic surgery and fillers, even physical traits become replicated through a population, uniquely independent of evolution. The meme, ultimately, presents the very paradigm of popism, of mainstream culture.

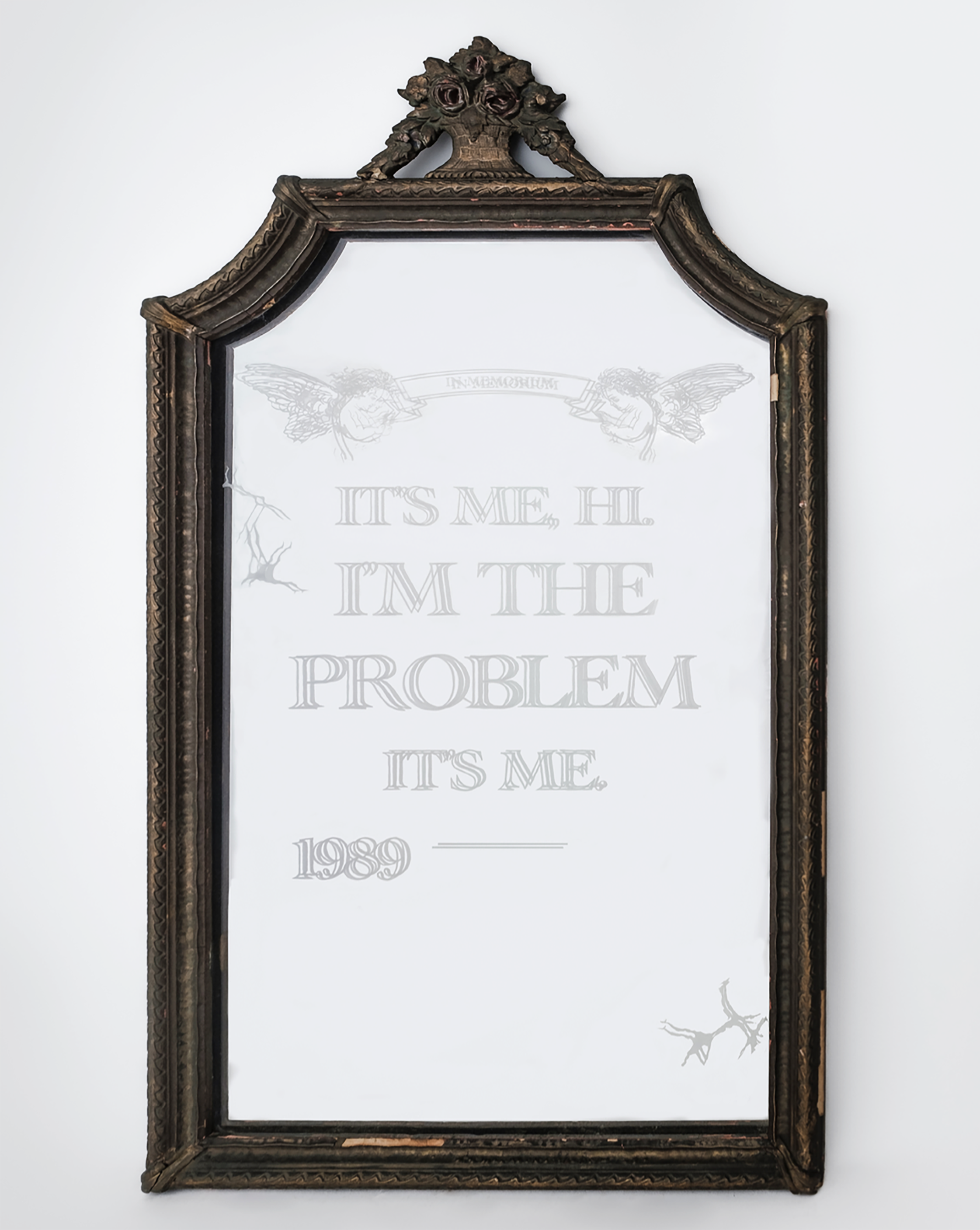

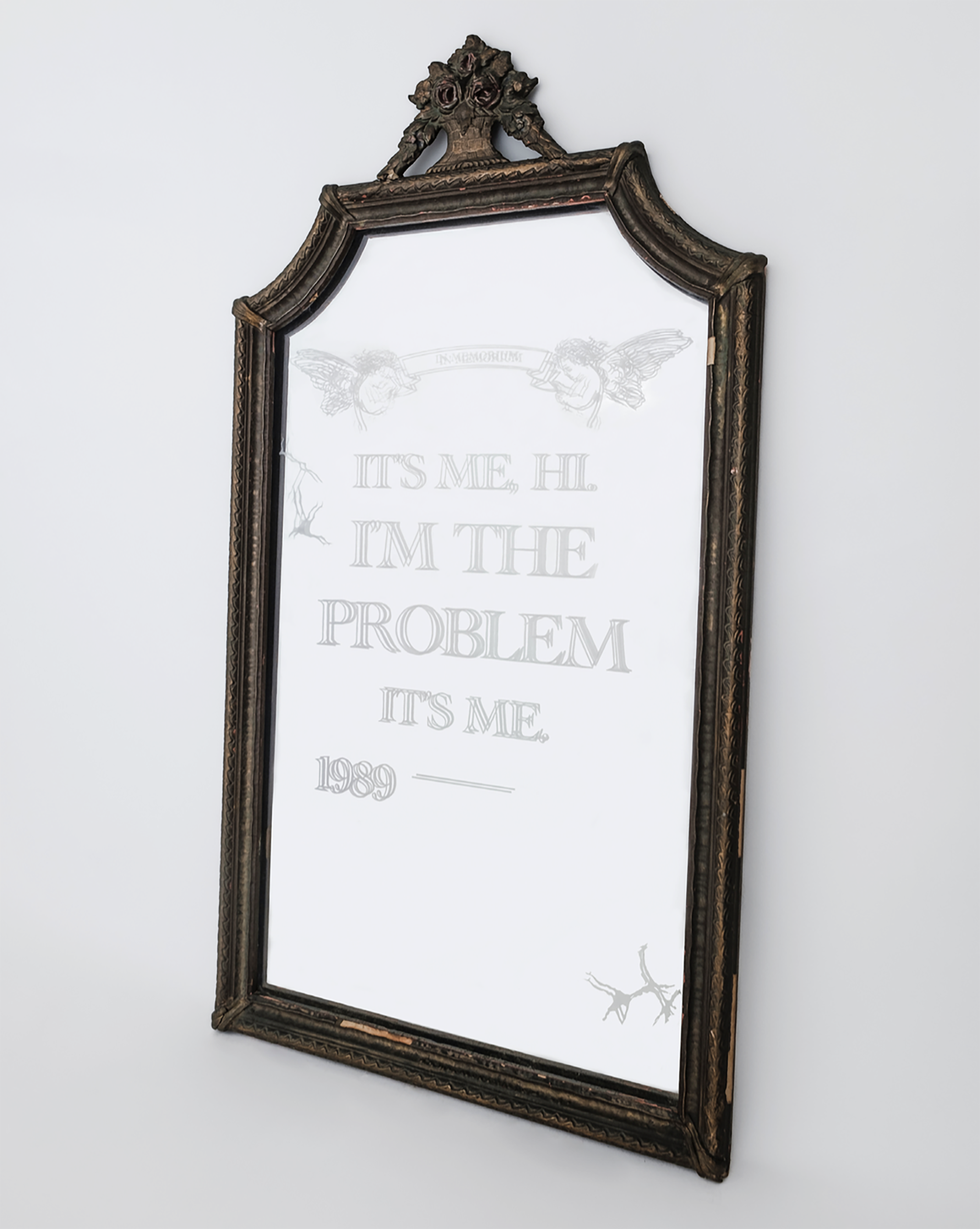

If the meme replicates the function of the gene, are there dominant and recessive memes? The points of origin for dominant memes are not necessarily the auteurs responsible for the phrasing, so much as the idolized mouthpieces of the phrases—though sometimes they are, in fact, one in the same. Why should so banal a phrase as “Why you so obsessed with me?” promulgate to such an extent that even so solipsistic a creature as I can cite the reference, appreciate the context, and recite the phrase in its original AAVE grammar to convey so many different states of feeling surveilled, by the other, by the mind’s eye, or by the male gaze both in the external world and in the mind of those socialized female in a culture of gendered violence and double-standards. The inherent dynamism of “it’s me, hi, I’m the problem, it’s me” has rendered itself indispensable in several years of memes both in mundane life and on the internet—a phrase so many of us turn out to identify with, including people who have no real talent for taking accountability.

When a phrase from pop culture becomes memed enough even to permeate my sphere of consciousness, I experience a dichotomy of belonging, and fear of forced conformity. To address this, and to stay authentic to my own compulsion to participate in these contagious expressions, I have extrapolated the nature of these memes through a technique Craig Owens’ describes as allegory, which “occurs when one text is doubled by another. . . . however fragmentary, intermittent, or chaotic the relationship may be; the paradigm for the allegorical work is thus the palimpsest” (Owens, “The Allegorical Impulse: Toward a Theory of Postmodernism,” page 3). By changing the physical context of these memes, verbatim quotes from frivolous pop songs suddenly refer to universal existential angsts: aging, mortality, the goose-step of time, the uselessness of resistance, the vanity of desire.

Jacques Lacan proposed that we spend our lives identifying with or against external stimuli as we approach the image. In this particular exploration of identity, I have attempted to create a dialectic in which one identifies simultaneously with and against external stimuli with the encounter of the self in the work of another. Furthermore, in my debut collection of traditionally postmodern work, I had to reckon with the fact that my very own existence—my very own family, my very own name—also qualifies as “camp,” which Susan Sontag states, “makes no distinction between the unique object and the mass-produced object. Camp taste transcends the nausea of the replica” (Sontag, Notes on Camp, 1964). In other words, camp includes references to pop culture—and the Getty family qualifies as such. Thus, I have extrapolated this series, both personal and universal, to explore new expressions of pop iconography in my very own blood.

-Kendalle Getty

Untitled

Multimedia

2024

Photo by Esteban Schimpf

Portrait of a Narcissist

Multimedia

2021

Photo by Esteban Schimpf

Portrait of a Morbid Mind I

Multimedia

2024

Photo by Esteban Schimpf

Sigil Face I

Multimedia

2024

Photo by Esteban Schimpf

Microaggression II

4 1/8” l x 4” w x 3” d

Multimedia

2023

Photo by Esteban Schimpf

Microaggressions III

4” l x 3.5” w x 4” d

Multimedia

2023

Photo by Esteban Schimpf

Microaggression IV

4 1/8” l x 4” w x 3” d

Multimedia

2024

Photo by Esteban Schimpf

Microaggressions V

3 3/4” l x 4” w x 3” d

Multimedia

2024

Photo by Esteban Schimpf

The Invisible Child

Multimedia

2022-2024

Photo by Esteban Schimpf